Health Inequalities in Scotland: Leaving No One Behind

This blog presents some data from our new report Changing mortality rates in Scotland and the UK: an updated summary (produced by David Walsh and Gerry McCartney). In doing so, it also offers some reflections regarding two recent reports on health inequalities in Scotland; the first from the Health Foundation and the second from Our Scottish Future. But first, we provide some important context.

It’s a quarter of a century now since Acheson reported on health inequalities in the UK, and on their underlying social and economic determinants; importantly, a quarter of a century since the UK’s first Minister for Public Health gave ‘permission’ to speak about policy and practice in these terms[1]. A quarter of a century too since the Scotland Act. It devolved powers which, it was believed, would allow key underlying determinants to be realigned so as both to improve health (lagging behind the rest of Britain), and, crucially, to reduce those health inequalities (also worse here than in the rest of Britain).

Soon, it will be 20 years since the GCPH was created, as part of the then Scottish Executive’s commitment to improve health while reducing inequalities – which were then still (as now) continuing to widen. GCPH’s remit was – and is – to produce and disseminate evidence and knowledge, and to connect that to policy and practice, with a view to influencing and supporting change.

The subsequent years have been, at best, ‘challenging’. From the ‘credit crunch’, to the financial crisis, to the ‘great recession’, to austerity, the COVID-19 pandemic, and now the cost-of-living crisis, in conditions which feel like recession, even if they do not quite yet meet the technical definition. As it all unfolds before us, there is a risk that it becomes somehow normalised, or, perhaps more worryingly, that we somehow choose not to see it for what it is. But the reality is that we have been, and are, living through something of a social catastrophe. And all the indications are that it is getting worse and will become worse still in the foreseeable future.

This is crystallised in different ways. One way is in the 'lived experience' reported in the media and feeding into research and policymaking. Another way is in the colder calculus of life expectancy and the related measure of (age standardised) mortality rates. And in the latter respect, the newest data being reported by GCPH, in Changing mortality rates in Scotland and the UK: an updated summary, charts the emergence of the catastrophe.

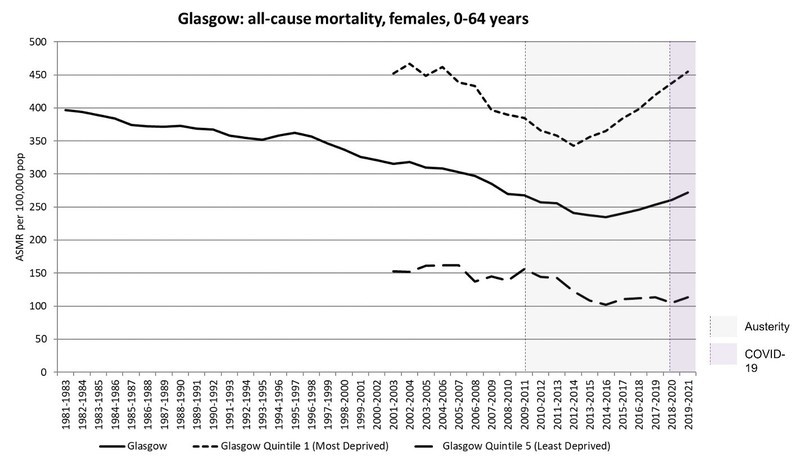

Let’s take a quick look at some of the most striking data. Figure 1, below, shows how mortality rates for women under 65 years in Glasgow stopped declining in the middle of the last decade and then rose – years before the pandemic. The rise for women in the most deprived areas is simply appalling.

Figure 1: Age-standardised all-cause mortality rates (females, all ages), three-year rolling averages, Scotland 1981-2021 (Source: Walsh D, McCartney G. Changing mortality rates in Scotland and the UK: an updated summary. GCPH: Glasgow; 2023).

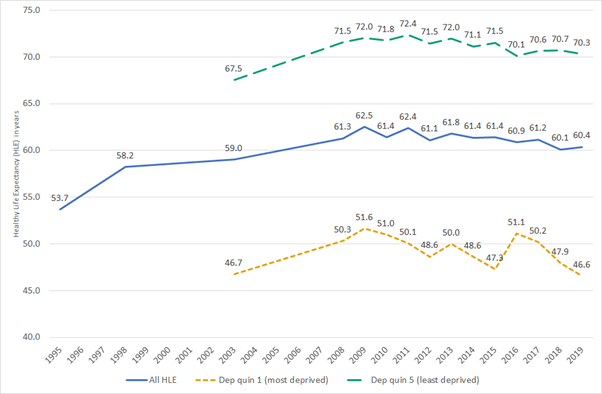

This is just one example of more general and truly shocking developments – which are unprecedented and should not be happening in a wealthy society. Figure 2 shows that even before the pandemic (2019), healthy life expectancy (a measure of the number of years lived in good health) in Scotland was lower than it had been in 2008. For those living in the 20% most deprived areas, it was lower than in 2004, and, at just 46.6 years, five years lower than had been the case in 2009. Even the richest 20% were faring less well than in 2008. All of this before COVID-19.

Figure 2. Healthy life expectancy (HLE), Scotland and 20% most and least deprived populations 1995-2019. (Source: Walsh D, Wyper G, McCartney G. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the age of austerity. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2022; 76: 743-745 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd)

But if the outcomes in terms of overall health and widening health inequalities (the poor are losing more than the well-off) are so catastrophic, it is not because we lack understanding and evidence, either about the causes or the policy solutions.

The evidence is abundant, clear, robust: health inequalities are extensions of underlying social inequalities. We know this from studies spanning both time (at least many decades) and place (countries, continents). The ‘fundamental causes’ of health inequalities are inequalities in income, wealth and power.

Thus, UK health inequalities decreased dramatically between the 1920s and 1970s – due to a corresponding reduction in inequalities in income, wealth and power, including increased social protection for the least well off. UK policies introduced later widened inequalities in income, wealth and power and, as a consequence, health inequalities. More recently, the UK Government’s austerity policies eroded social protection, thus, as our research has shown, widening mortality inequalities further.

The same scientific evidence indicates viable solutions; measures to narrow inequalities in income, wealth and power top the list. Ten years ago, building on work from Glasgow University, NHS Health Scotland (since integrated into Public Health Scotland) undertook a review of all the international evidence of ‘what works’ in reducing health inequalities. Effective policies were laid out on three levels:

- Policies to narrow fundamental inequalities (e.g., progressive taxation to redistribute income, a robust social security system to protect the poorest);

- Measures to address ‘wider environmental influences’ (such as improving housing quality, and taxing unhealthy commodities, like alcohol);

- Actions to mitigate particular experiences of inequalities (e.g., targeting services for high-risk groups, such as homeless people).

Based on the extensive, accumulated science, the report made it clear that health inequalities would only be effectively reduced if the first set of actions was implemented. Without that, strategies would fail. This is not opinion, but knowledge, founded on evidence.

In the current circumstances – now, more than ever – it is vital that all of those who seek to intervene to support progress in reducing health inequalities clearly and effectively convey this knowledge. And there are many who are seeking to intervene. At times, it can seem hard to keep up. In later January alone, two more reports emerged: one from the Health Foundation, and another from Our Scottish Future. Both reports have good qualities – with the Health Foundation, in particular, highlighting the socioeconomic drivers of inequalities, including the major impact of austerity. But there are also significant weaknesses.

Most importantly, neither report adequately conveys what is known about the policy responses required to tackle intensifying inequalities. Emphasised are familiar – and of course important – themes around co-operation amongst partners, bridging the implementation gap, empowering communities, acting together to support delivery, and so on. Indeed, the Health Foundation suggests, in contradiction to the recent report of the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee of the Scottish Parliament, Tackling Health Inequalities in Scotland (September 2022), that no new strategy is required. Given that the aforementioned Committee found that there is in fact currently no strategy to speak of, then that would mean no strategy at all. Rather, the Foundation’s message seems to be that all the relevant organisations and agencies should get on, in a more purposive way, with doing what they have been supposed to be doing for some time.

At risk of repetition, many of the measures proposed in these recent reports are necessary and important, but they are generally not new and have not, and in and of themselves will not, narrow health inequalities. That much is known, and it also needs to be conveyed clearly, as an essential basis for any effective and sustainable progress.

And here there is another important consideration: the Scottish Parliament certainly does have powers to implement policies to impact on the fundamental causes of health inequalities. Helpful and important policies have been introduced, such as the recent Scottish Child Payment to help poorer families, though the STUC has made the case that current tax raising powers could, if used, resource more. But many of the most relevant and potentially impactful powers – around taxation, social security and other key areas such as employment legislation – are reserved to the UK Parliament.

Facing a cost-of-living crisis, following both a pandemic and more than a decade of health inequality generating austerity policies, it is important to remember that Scotland and the UK are wealthy societies. But, income, power and resources are ill divided, making society as a whole less healthy than it should be, and increasingly unequal in health too. That is the challenge for policy makers. And it needs to be presented, clearly and consistently, to all of the relevant policy makers, by all who claim to speak in terms of knowledge, based on evidence.

[1] Under the previous government, only talk of ‘variations’ had been permitted in government.

Previous

February e-update

Back to