What can drive change?

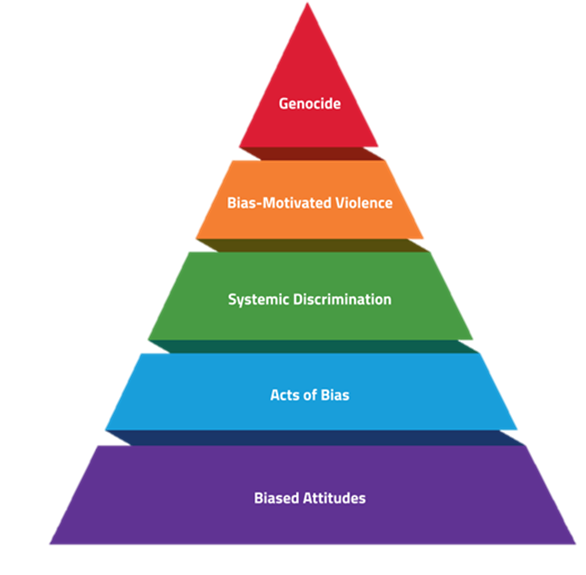

The Pyramid of Hate demonstrates how bias even at a small-scale level is linked to, and can lead to, extreme violence against a marginalised group by normalising attitudes that dehumanise that group. Each level of the pyramid is linked, and the lower attitude-based levels are part of the process of ‘othering’ women, which supports the more openly violent higher levels.

Even those who do not think of themselves as hateful towards women, including women, can contribute to this system of hate that perpetuates gendered inequalities and violence. Since this problem comes from various levels, holistic action is required on several levels simultaneously.

Pyramid of hate diagram adapted from Anti-defamation League (ADL). Download this diagram and more information.

Pyramid of hate diagram adapted from Anti-defamation League (ADL). Download this diagram and more information.

Individual

As individuals, we have a responsibility to educate ourselves about the processes of marginalisation that we may be contributing to. This begins by listening to those who are marginalised, either because of their gender, or for any other reason. However, individual personal changes alone cannot rewrite societal power structures that have been entrenched for centuries. Individual responsibility needs to be supported by more communal work on education, leadership, and power.

Education

Research shows that the more children receive messages that gender matters, the more likely they are to make assumptions about gender. As the pyramid of hate illustrates, this othering has an impact on behaviour. The more strongly boys believe gender stereotypes, the more likely they are to engage in sexist and misogynistic behaviours later in life. At the same time, girls learn that these behaviours are normal, and that is it their responsibility to keep themselves safe.

The counter narrative is to educate boys that there are no limitations and they are free to learn how to be themselves. This can be achieved in a way that doesn’t marginalise or demonise boys, and which supports them in challenging all forms of gender stereotypes.

How we educate young people about violence against women is changing. The Glasgow Violence Against Women Partnership have created educational videos on topics like domestic abuse and coercive relationships to be discussed in schools.

Power Sharing

Gender equality is not just about making better decisions for women, girls, non-binary people and other marginalised groups. It is also about sharing power and meaningfully involving them in decision-making processes. The Young Women Lead (2021) report calls for ‘collaborative partnership’ in designing transport services, and this approach can be taken more widely. For example, Glasgow City Council’s goal that the “experiences of women and girls inform the planning and activity to eradicate gender-based violence”.

As this is, at its roots, an issue of power, we need to change how we view power and who can hold it. This includes changing how we structure our economy. The Caring Economy, proposed by the Women’s Budget Group, would put care at the centre of our economic decisions – recognising that it is essential, undervalued and most often undertaken by women. The idea of a Wellbeing Economy similarly questions what we might achieve if we structured and shared power differently.

Leadership

In the Scottish Gender Equality Index (which measures gender equality on a scale of 0-100 across multiple domains) the power domain has the lowest score (44), highlighting that woman have less influence in political, social, and economic decision making in Scotland compared to men.

When primary power is held by men, then what is implemented to promote and protect females will inevitably remain a watered-down version. Thus, to achieve gender equality across society, women’s participation in power and leadership must be addressed.

A key barrier women encounter in positions of power, but also across the workforce in general, is the need to balance work with family and caring commitments: which can disproportionately slow progression of their career. For example, the May 2021 Scottish Parliamentary election saw the most gender equal result ever - women made up 48% of the parliament. But that same year, three female MSPs stood down citing difficulties with managing family life and their role. In a workforce that is predominantly female, Glasgow City Council reported that 90% of their flexible working applications were from women looking to achieve a work-life balance, or to balance caring/family commitments.

Roles and workplaces must be redesigned to enable flexible working arrangements and non-traditional career paths, for men and women, so that the burden of care can be equally shared. Policies (e.g. shared parental leave) are a useful tool for progressing gender balance but they alone won’t guarantee better outcomes. Leadership, which is committed to and promotes these arrangements is vital to normalise uptake across levels and genders.

Summary

Achieving gender equality is not an “easy win”. As this series of blogs has evidenced, there are multiple systemic failures to address. Individual, group, and system responsibilities are inter- and co-dependent, and change requires all of these at once. It’s a daunting task, but ultimately, as a society, we cannot afford to lose energy for it.

There’s more noise than ever before around gender inequalities; we have new activists and campaigners fighting for change and justice; more men, organisations, politicians, and people in power are joining the conversation. Change is possible, and it is possible even within our generation, but only if we can keep this momentum up and continue to garner support, and only if those in power are ready to embrace this change.

This blog was co-authored by Katharine Timpson, Mairi Young and Mohasin Ahmed.

Read the first blog in this series on gender inequalities.

Read the second blog: Women have a right to the city

Read the third blog: Women’s public safety is a health issue

Read the fourth blog: Systemic failures contributing to gender inequality

Read the fifth blog: Gender inequalities and intersectionality