The challenge of an unequal world

Michael Marmot’s new book The health gap: the challenge of an unequal world was published last week. It’s a good read, full of evidence and examples from across the world of the impact of inequality on health, and what can be done about it. Glasgow is mentioned frequently as an example of a city where stark inequalities in a generally affluent society have an impact on health and life expectancy.

For an organisation like the GCPH, a book like this is a welcome endorsement of an approach which focuses on inequality as well as health, and on the ‘causes of the causes’ – the social and economic contexts in which people live and grow up. But it is also a challenge and a prompt to reflect on whether we are doing the right things and doing all we can.

So, what is the current situation in Glasgow?

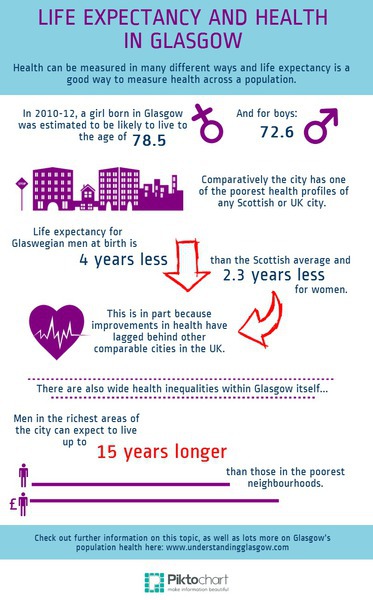

The infographic below describes life expectancy in the city – it has improved for everyone but there is still a 15 year gap between life expectancy for men in the richest and poorest neighbourhoods. The often quoted figure of 54 no longer stands but there are significant differences between neighbourhoods.

Gradient and patterns of health

Professor Marmot’s book highlights the gradient in a range of outcomes – health, education – relative to wealth, a pattern repeated across the globe, within and between countries. Those in the ‘middle’ fare better than those at the bottom, and worse than those at the top. Inequality is not just a matter of rich versus poor, but of differences across the social spectrum which affect everyone.

There are common issues of power and control which have a greater impact than absolute income or poverty. This is a central theme of the book which states: “The gradient changes the discussion fundamentally. The gradient implies that the central issue is inequality, not simply poverty.” In terms of a response then, action is needed which has an effect across the spectrum (“proportionate universalism”) not just targeted activity at the ‘bottom’.

This can be seen clearly in the figures for Glasgow; it is not a case of some neighbourhoods with terrible outcomes and everyone else doing OK, but a gradient across these.

The GCPH aims to take a ‘population health’ approach. What do we mean by that? It means understanding and demonstrating the patterns of health across the population; focusing on inequality and not just average health improvement; understanding changes in population and how those affect health; seeing individuals in the context of wider social, economic and environmental influences; understanding change across the life-course, and supporting services to take account of population needs. Above all it means working in partnership.

Challenging questions

Michael Marmot’s book supports these sorts of approaches, but also makes us ask some challenging questions. Do we get the balance right between describing population effects and supporting solutions? Are we consistent in our own language and approach about poverty and inequality and tackling the gradient? What does all this mean for place-based approaches and targeting of resources? Is proportionate universalism at the heart of what we do and can we demonstrate what it means in practice? Do we understand enough about social cohesion and empowerment across the population? Are we being proportionate in addressing the issues which have the biggest effects, however difficult these are? And are we supporting action with enough urgency?

The book is characterised by a note of optimism: that some countries are already doing what’s needed, that we have the evidence of what can be done, and that things can change quickly. So we will continue to conduct research, facilitate and stimulate the exchange of ideas, fresh thinking and debate, and support processes of development and change; and above all, continue to ask ourselves and others these questions to bring about change.

Previous

September e-update

Back to