Framing the conversation - talking about poverty and inequalities

Talking about poverty and inequalities is an important conversation for everyone to be a part of but how those conversations are framed can be more of a challenge.

This was the focus of a recent Glasgow Centre for Population Health in-house workshop. based on learning from a JRF-commissioned FrameWorks Institute study on ways of talking about poverty to better influence the public, media and policy-makers.

Run in partnership with the Poverty Alliance, this workshop asked participants to consider these new ways of ‘framing’ our messages based on the evidence from the FrameWorks Institute. It would be fair to say that some of the strategies and approaches presented both challenged and then changed the way I think about this.

Frances Rayner, Communications Officer at the Poverty Alliance introduced a range of different poverty-framing strategies. By making a moral case and leading with values (particularly compassion and justice), you can achieve a change of mindset that doesn’t require a big shift in approach or understanding. For example, the phrasing below is hard to argue against:

'As a society, we believe in justice and compassion. But right now, millions of people in our country are living in poverty. We share a moral responsibility to make sure that everyone in our country has a decent standard of living and the same chances in life, no matter who they are or where they come from.'

Other strategies were much harder to get my head round. I have always thought that headlining facts and ‘myth busting’ are helpful tools, and indeed necessary, in changing understanding and thinking in any area… I was wrong. As Frances explained, being shown to be wrong is more likely to strengthen your original stance or opinion than change your mind. This is because being told you’re wrong activates the same area of your brain that is activated by pain and elicits a fight or flight response.

It isn’t the case that we shouldn’t use facts or evidence, rather that we should consider where and when we use them. In practice, this might mean not leading or opening a piece of writing with facts and evidence but use them later to back-up or reinforce the points you make. An example of this would be to start with the story we’re trying to promote: "In our society, we believe in justice and compassion. It is not right that a fifth of our population lives in poverty… We need to redesign the way our economy works to free people from the grip of poverty" before introducing facts and statistics.

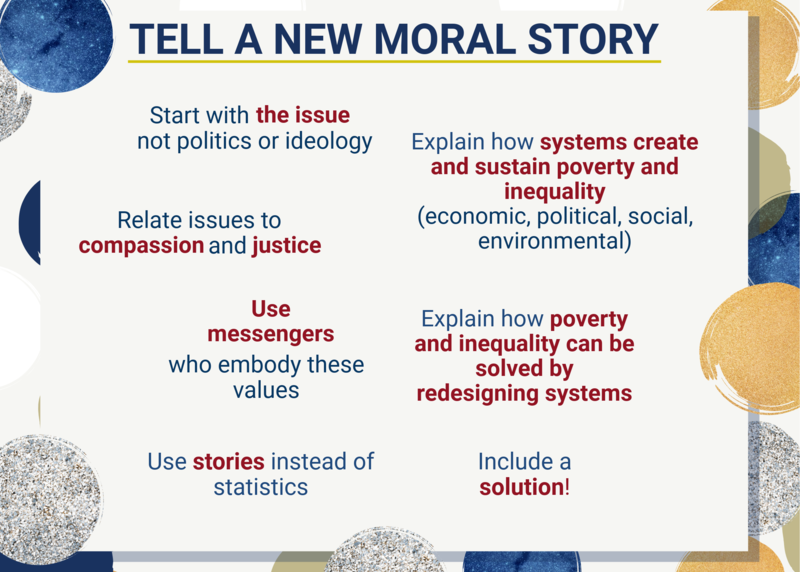

Although this has changed how I think about this, putting it into practice is going to take some practise! Below is a list of the ten FrameWorks approaches to telling a new story that Frances shared with us:

- Start with poverty, not politics or ideology

- Say why tackling poverty matters by relating to shared values of compassion and justice

- A story is brought to life by messengers who embody these values

- Explain how poverty can be solved by positioning, i.e. 'the economy as a designed system that can be re-designed' or 'benefits as helping to loosen poverty’s grip'

- Use examples, rather than statistics to demonstrate poverty’s characteristics and impacts

- Show how we all rely on public systems and paint a clear picture of what they look like

- Counter fatalism, with clear solutions that make a tangible difference

Following on from this, the GCPH’s Lynn Naven presented findings from another FrameWorks Institute study on how the underlying social determinants of health are positioned in the media and by different organisations. Lynn highlighted many examples of healthcare being presented as the answer to tackling poor health, rather than emphasising the huge importance of social factors in supporting health and wellbeing. The media also has a tendency to use crisis-laden language which has the effect of casting doubt on the public sector's ability to make a real difference.

Thankfully there are a number of things that can be done to tell stories about health in a different way. In an exercise designed to put our new learning to the test, we were given a number of different health-focused newspaper articles and asked to rewrite them, changing the dominant discourse to a more positive one.

This practical exercise did really make me think differently about how and what I write and say, as well as viewing what I read more critically. The way we talk about poverty and the social determinants of health influences public opinion. This is why we have to pay attention to using the right language to increase understanding of how poverty happens and what can be done to address it.

It is going to take practise before I am confident and comfortable in using the strategies and tools that we used during this session. However, for me, it is important that I do learn to use them and to challenge myself and others to change how we think, write and talk about poverty and inequalities.