The unprecedented rise of mortality across poorer parts of the UK

Because of the pandemic of 2020 people are worrying about their health and the health of those around them more this year than has been the case for many years.

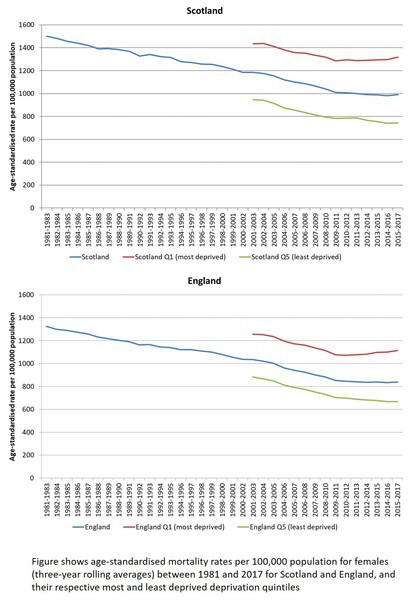

However, in the years immediately prior to the pandemic, the health of women in the UK, when measured using age standardized mortality rates, was hardly improving at all. For men it was only improving ever so slightly, about three times more slowly than it had improved during the 1980s and 1990s and five times more slowly than in the 2000s! In contrast to how acutely aware we are of the pandemic, most people were unaware of these changes because they were not the subject of news bulletins.

This is because slow changes in population health do not create news stories. However, it is truly shocking, as this BMJ Open paper reveals, that in poorer parts of the UK in the six years up to and including 2017, mortality rates actually rose. Outside of wartime, pandemics and epidemics, increases in mortality rates are unprecedented in the UK in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This rise in deaths has coincided with the imposition of austerity which has most harmed people in poorer cities.

In Scottish cities such as Dundee and Aberdeen, mortality rates worsened for both men and women in the years shortly after the Westminster coalition government was elected in 2010, and they continued to worsen during those years when the Conservatives were in power alone from 2015 onwards. In England too, for men in Liverpool and women across Birmingham, mortality rates rose.

In all the most deprived areas of Scotland and Northern Ireland, combined mortality rates rose in the second decade of the twenty-first century quickly, after having improved so very quickly before. In England there was no improvement in male rates in the poorest areas, and so the gap between them and the more affluent areas widened; for females in England, however, death rates among the poorest again increased (see Figure below). Respiratory disease, cancers and what have been called ‘diseases of despair’ rose abruptly in the poorest parts of Scotland in the years immediately prior to 2017. Before 2013 there had been such great improvements.

It cannot be stressed enough that these changes were unprecedented. The 2020 pandemic is not unprecedented – the UK has suffered many pandemics before including pandemics with similar mortality tolls in the 1950s and 1960s, and higher mortality rates for younger people then than in 2020. However, the deterioration of the health of the population in the decade before the pandemic struck meant that when it struck, we, and especially those in the poorest places, were weaker than before.

When you look at the maps of areas which suffered the most in 2020, think back to this paper and which areas had already seen mortality rates rising year on year before the arrival of any new disease into the UK.

Graph source: Walsh D, McCartney G, Minton J, et al. Changing mortality trends in countries and cities of the UK: a population-based trend analysis. BMJ Open 2020;0:e038135. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-038135

Graph source: Walsh D, McCartney G, Minton J, et al. Changing mortality trends in countries and cities of the UK: a population-based trend analysis. BMJ Open 2020;0:e038135. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-038135